[B]eyond some of her work and her unforgettable image — dark-haired, piercing-eyed, flower-crowned — I didn’t know enough about the Mexican artist and icon Frida Kahlo until the 2002 biopic “Frida,†starring Salma Sayek, in a stirring performance examining her life. That movie, for me, ignited an admiration for the artist,who died in 1954 at the young age of 47.

[B]eyond some of her work and her unforgettable image — dark-haired, piercing-eyed, flower-crowned — I didn’t know enough about the Mexican artist and icon Frida Kahlo until the 2002 biopic “Frida,†starring Salma Sayek, in a stirring performance examining her life. That movie, for me, ignited an admiration for the artist,who died in 1954 at the young age of 47.

Throughout her life, Frida Kahlo was a maverick who staunchly held faith in herself and her art, refusing to bow down to her culture or her time. Her strangely colorful and beautiful paintings, the bulk of which were self-portraits, were described as “surrealist,†and while depicting a dream-like world and imagery were pronounced by the artist as perfectly real.

Frida Kahlo survived childhood polio, but a bus accident at the age of 18 that impaled her and crushed her pelvis, left her with chronic pain and recurring health problems the rest of her life. But her confinement, isolation and pain fueled her art. Her art and her passion were also inspired by the love of her life, her mentor, the Mexican painter Diego Rivera, whom she eventually married. His notoriety in the art world led to years of travel and eventual fame for Frida herself, but theirs was an often troubled union, as they were both fiery, strong-willed and unfaithful. But they always returned to each other, and beneath any recurring instability, there was still a solid foundation in their love of art and home. Home was La Casa Azul (Blue House), a house painted in a brilliant tempura blue to “ward off evil spirits,†and within that house, along with Frida’s enthusiasm for color, beauty, plants and animals (she kept pets that included monkeys), there, too, was regular celebration, laden with lively foods.

Frida Kahlo survived childhood polio, but a bus accident at the age of 18 that impaled her and crushed her pelvis, left her with chronic pain and recurring health problems the rest of her life. But her confinement, isolation and pain fueled her art. Her art and her passion were also inspired by the love of her life, her mentor, the Mexican painter Diego Rivera, whom she eventually married. His notoriety in the art world led to years of travel and eventual fame for Frida herself, but theirs was an often troubled union, as they were both fiery, strong-willed and unfaithful. But they always returned to each other, and beneath any recurring instability, there was still a solid foundation in their love of art and home. Home was La Casa Azul (Blue House), a house painted in a brilliant tempura blue to “ward off evil spirits,†and within that house, along with Frida’s enthusiasm for color, beauty, plants and animals (she kept pets that included monkeys), there, too, was regular celebration, laden with lively foods.

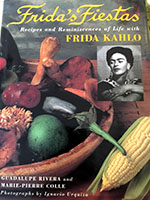

In “Frida’s Fiestas: Recipes and Reminiscences of Life with Frida Kahlo,†Guadalupe Rivera, daughter of Frida’s Diego, recounts those celebrations — of anniversaries, baptisms, birthdays, holidays, saints’ days, historical dedications and spiritual honorings. The book is divided into 12 months of fiestas, featuring menus and beloved recipes that would be served.

In “Frida’s Fiestas: Recipes and Reminiscences of Life with Frida Kahlo,†Guadalupe Rivera, daughter of Frida’s Diego, recounts those celebrations — of anniversaries, baptisms, birthdays, holidays, saints’ days, historical dedications and spiritual honorings. The book is divided into 12 months of fiestas, featuring menus and beloved recipes that would be served.

One chapter is Frida and Diego’s anniversary, another a feast for national holidays, another, Day of the Dead, a Candlemas baptism, and a “the meal of the broad tablecloths,†which was an extra large gathering of friends, acquaintances and family. The menus of these feasts are generous, sometimes offering two soups, two meats, several desserts. Recipes within are sensory bursts of culinary inspiration, and include shrimp patties, red snapper soup, chilled pigs feet, fish baked in acuyo leaves, squash blossom quesadillas, limes stuffed with coconut, yellow and red mole sauce, pine nut flan, cookies called cat’s tongues. The book is no less colorful than the recipes, featuring photos of the foods as they would be presented in Frida’s day, along with photos of Frida and Diego and their art and their life. The book is a feast in itself, to be enjoyed again and again on long afternoons and evenings to enjoy a biography of Frida, the artist, through food.

For the month of January, an intriguing-looking bread lay like a long looped blanket on the table for the “feast of the Three Kings,†or, the Epiphany, celebrated on Jan. 6. I’ve long loved the idea of “little Christmas,†but alas, it is little celebrated in this country. For Frida’s January feast, the Rosca de Reyes or Three Kings Bread loomed large among a menu including tacos with sour cream, flautas, red and green chalupas, macaroons, eggnog mold and hot chocolate drink. The bread, resembling a crown, is decorated with colorful fruits and candied peels and contains a porcelain doll (if you can find one), to represent the Christ child. While a beautiful recipe is presented in the book, it was also revealed that Frida often bought the bread at one of her favorite bakeries in Mexico City.

For the month of January, an intriguing-looking bread lay like a long looped blanket on the table for the “feast of the Three Kings,†or, the Epiphany, celebrated on Jan. 6. I’ve long loved the idea of “little Christmas,†but alas, it is little celebrated in this country. For Frida’s January feast, the Rosca de Reyes or Three Kings Bread loomed large among a menu including tacos with sour cream, flautas, red and green chalupas, macaroons, eggnog mold and hot chocolate drink. The bread, resembling a crown, is decorated with colorful fruits and candied peels and contains a porcelain doll (if you can find one), to represent the Christ child. While a beautiful recipe is presented in the book, it was also revealed that Frida often bought the bread at one of her favorite bakeries in Mexico City.

I had made a similar bread — a King Cake — for a February 2012 blog entry. That bread, gaudy with glittery Mardis Gras-colored sugar, symbolized religious respects but also a decadence to be indulged in prior to Lent. The Rosca de Reyes seemed earthier and more connected to the season falling between late December and early January.

I had made a similar bread — a King Cake — for a February 2012 blog entry. That bread, gaudy with glittery Mardis Gras-colored sugar, symbolized religious respects but also a decadence to be indulged in prior to Lent. The Rosca de Reyes seemed earthier and more connected to the season falling between late December and early January.

I went to my local Mexican market and discovered Rosca de Reyes rings all over the store. I loved that I could see a culture honor the tradition. Each bread even came with its own “baby† in plastic form. I bought a small rosca to sample at home. It had strips of colored dough and fruit peels adding decoration to the top. The bread was soft and slightly sweet, that buttery, egg-y sweet roll type of bread, perfect with butter — and coffee — in the morning.

in plastic form. I bought a small rosca to sample at home. It had strips of colored dough and fruit peels adding decoration to the top. The bread was soft and slightly sweet, that buttery, egg-y sweet roll type of bread, perfect with butter — and coffee — in the morning.

But I was anxious to tackle a Rosca de Reyes of my own. I had candied cherries and citron from fruitcakes I made in November and December, some candied orange peel from a chocolate shop adventure. I purchased some dark, mud-brown figs, that, when sliced, released such a full rich perfume, I could not stop thinking of all the ways I could use them. I was excited to have them, modest and rustic, amid the more colorful fruits for the bread.

The bread dough itself was an egg and butter rich brioche, made a little sweeter and spicier with the addition of raisins, cinnamon and anise seed.

It rose beautifully over the course of two hours, and I gleefully punched it down, rolled it into a length and shaped it into a circle

The fruits adhered to the ring in a pattern that I let present itself, maybe not unlike a painter allows the brush to move over a canvas. After rising again, the dough was brushed with egg, sprinkled with sugar and baked off.

Once baked, the rosca is a thing to behold, quite large and colorful. It is soft, moist and tender, punctuated nicely with raisins and spice. It should be served to a table of people, yet I, as the experimental and reclusive baker, chalked this one up to another private experiment, to be shared in writing. But it’s a new year. My own fiestas might be coming, I think. Perhaps I have been preparing for them this whole time.

Rosca de Reyes

From “Frida’s Fiestas: Recipes and Reminiscences of Life with Frida Kahloâ€

by Guadalupe Rivera and Marie-Pierre Colle (1994)

3 1/2 cups flour

1 envelope active dry yeast, dissolved in 5 tablespoons warm milk

3/4 cup sugar

7 eggs

4 1/2 ounces butter, softened

1/4 cup warm milk

Salt

2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon anise seeds

3/4 cup raisins

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 small porcelain doll

3 ounces dried figs, cut in strips

1/3 cup candied cherries

1/2 cup candied citron, cut in strips

1/2 cup candied orange, cut in strips

1/2 cup candied lemon, cut in strips

1 beaten egg

Sugar

Mound the flour on the counter or in a bowl and make a well in the center. Fill the well with the softened yeast, sugar, eggs, butter, milk, a pinch of salt, the cinnamon, anise, raisins and vanilla. Mix into a dough and knead for about 20 minutes until the dough pulls away from the counter. Shape the dough into a ball. Brush it with softened butter, and place in a greased bowl. Cover with a cloth and let rise in a warm place for 2 1/2 to 3 hours, until doubled in bulk.

Place the dough on a floured surface, knead lightly, and shape into a ring. Poke the doll into the dough and arrange the ring on a buttered baking sheet. Decorate the ring with candied fruit and let it rise again for 1 1/2 hours, until doubled in bulk. Brush with beaten egg, sprinkle with sugar, and bake in a preheated 375-degree oven for 40 minutes, or until done. You know the rosca is done when the bottom sounds hollow when tapped.

Blogger’s Note: If you cannot find a porcelain doll, you can use a plastic one, just DO NOT insert the doll prior to baking, as it will melt. The baby can be inserted from underneath once the rosca is baked and cooled.