Before the Internet, before Food Network, before Julia Child, before TV, there was a writer of food and her medium (Egads!), was the humble printed word. There was a writer whose words were so potent, her prose so swarthy, that, upon seeing her work, publishers decided a woman would never write like that, so Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher became MFK to become more palatable for the general public’s consumption.

Before the Internet, before Food Network, before Julia Child, before TV, there was a writer of food and her medium (Egads!), was the humble printed word. There was a writer whose words were so potent, her prose so swarthy, that, upon seeing her work, publishers decided a woman would never write like that, so Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher became MFK to become more palatable for the general public’s consumption.

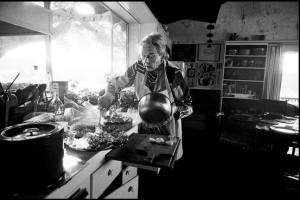

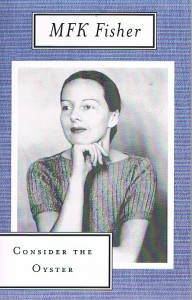

Once the work of MFK Fisher became widely known and read, so did her image. The photographs of this California writer could certainly not hide her gender – MFK was as lovely and glamorous as any starlet of the time. But it was her words that transcended her time and her gender. The girl could cook and the girl could write. She honed her writing chops very early, writing for her father’s newspaper. She honed her cooking chops everywhere from her grandmother’s kitchen in Southern California to as far afield as Provence. Her first book, “Serve It Forth (Art of Eating),†was published in 1937.

Fisher (who died in 1992) became the author of many books of essays and memoirs (among them “An Alphabet for Gourmets

Fisher (who died in 1992) became the author of many books of essays and memoirs (among them “An Alphabet for Gourmets,†“Consider the Oyster

,†and “The Gastronomical Me

â€). Her work made her an icon in the food genre. But her writing — elegant, witty and nearly flawless, can stand up against any literary work in any genre.

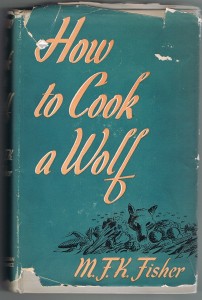

I found a first printing of Fisher’s “How to Cook a Wolf†in an antique mall in Southern California a number of years ago, but only recently took it from the shelf, dusted it off and dipped in. Books, like many things, sometimes find their way into our hands at the right time. Perched on the edge of a precipice of post-birthday goals I needed reassurance from the right voice to move forward. Reading this aged volume – dusty with the sweet smell of decaying pages — was like time travel to the reassuring and more sure-footed kitchen of an earlier era. MFK hailed from a time when women were both elegant and hardy – they knew how to make loaves out of anything and they could heat their homes with tin cans. Yet they knew how to be lovely – they kept mirror compacts in their kitchen cupboards and knew how to rid their hands of the stink of onions by rinsing them under cold water (two tips from Fisher’s book).

“How to Cook a Wolf†was published in 1942, when the world was at war. Americans were asked to button up and brace themselves. There were shortages on food and fuel. There was no room in the home for frivolity or gaiety and certainly no waste. Still, a lilting voice on the home front was needed. The book is both meant to guide and uplift during a troubling time, offering advice on how to make the best out of shortages and conservation and the threatening unknown. One can be thrifty without losing one’s soul. The “wolf†frequently referred to throughout the book, can be considered hunger, looming and sniffing. But beyond real, physical hunger, I think the “wolf†meant by MFK could also be considered hunger of the spirit, of the psyche, a desperation and helplessness to keep at bay.

Reading MFK Fisher is page after page of pleasant surprises, not merely in what she writes about, but in how she writes. Her vocabulary is peppered with words not normally found in food writing, words and phrasing both perplexing and perfect, like “odorous,†“fuming,†“jolly poaching,†“gastronomical voodoo†and even “rich bitches.†She describes a potato skin as a “delicate coat,†and the best gravy as “innocent of flour.†She seems to effortlessly trail strands of words together like fine pearls; “Probably one of the most private things in the world is an egg until it is broken.â€

Beyond the poetry of her work in this book is the true rendering of the times. Tucked into the kitchen of “How to Cook a Wolf†is the mind and heart of those living during World War II. The advice renders staggeringly the thrift by which people lived, saving canned fruit or cooked vegetable juices in a gin bottle in the refrigerator (to drink for vitamins), making soap out of grease (“purely functional and looks ugly and smells worse,†she writes), how to make better use of the oven and stove by making hayboxes, tightly closed boxes packed with hay into which one placed one’s food that had just been brought to a boil to continue to cook without the use of fuel or electricity. There are tips on how to handle iron rations and prepare foods in blackouts. There are ways given to get more mileage out of dishes, say, by adding breadcrumbs to scrambled eggs. One chapter emphasizes the care and feeding of pets, which were, in wartime in Europe, often encouraged to be killed.

What is applicable from a 1942 artful household volume today? Much, whether as simple as rubbing a chicken with lemon to clean it rather than washing it underwater or striving for less waste and stretching our resources. We can consider a good apple and some warmed walnuts a fine dessert. We can look our best, should company come by, yet know that, even if we don’t look so hot after slaving over a hot stove, MFK says, “I’ll not care, really, even if your nose is a little shiny, so long as you are self-possessed and sure that, wolf or no wolf, your mind is your own and your heart is another’s and therefore in the right place.â€

There is much to delight, inspire and consider in all of the chapters of “How to Cook a Wolf.†I’m particularly fond of the section, “How to Rise Up Like New Bread.†I’ve never read anything so moving about the baking process:

“It does not cost much. It is pleasant: one of those almost hypnotic businesses, like a dance from some ancient ceremony. It leaves you filled with peace, and the house filled with one o the world’s sweetest smells. But it takes a lot of time. If you can find that, the rest is easy. And if you cannot rightly find it, make it, for probably there is no chiropractic treatment, no Yoga exercise, no hour of meditation in a music-throbbing chapel, that will leave you emptier of bad thoughts than this homely ceremony of making bread.â€

(Upon reading that, AWS has no choice but to make 2012 a “bread-of-the-month†year!)

I wanted to cook something MFK cooked, and in reviewing any book of cookery, I believe at least two or more dishes from the book should be made. I found the names of the two recipes I tried immensely appealing (in my dark-humored way).  One was called “Eggs in Hell†— well, how in the hell could I not make this dish? Eggs are poached in tomato sauce and served on toasted bread. This sounded terribly appetizing, in fact, enough to make the wolf in my stomach growl a little. The recipe is easy to make, with an interesting tip of skewering a garlic clove on a toothpick prior to sautéing it, then using the pick to fish the garlic out. I found the cooking time to be a tad long for how I like my eggs (if you like them hard, keep the cooking time at 15 minutes). But I used MFK’s suggestion of adding the eggs to the hot tomato sauce, putting the lid on the pan and turning off the heat. The eggs are cooked within 8 to 12 minutes. I pan-grilled my French bread in olive oil and served them with the tomato-y, Italian-seasoned eggs. It was a delicious, hearty lunch and would make a great brunch for guests.

One was called “Eggs in Hell†— well, how in the hell could I not make this dish? Eggs are poached in tomato sauce and served on toasted bread. This sounded terribly appetizing, in fact, enough to make the wolf in my stomach growl a little. The recipe is easy to make, with an interesting tip of skewering a garlic clove on a toothpick prior to sautéing it, then using the pick to fish the garlic out. I found the cooking time to be a tad long for how I like my eggs (if you like them hard, keep the cooking time at 15 minutes). But I used MFK’s suggestion of adding the eggs to the hot tomato sauce, putting the lid on the pan and turning off the heat. The eggs are cooked within 8 to 12 minutes. I pan-grilled my French bread in olive oil and served them with the tomato-y, Italian-seasoned eggs. It was a delicious, hearty lunch and would make a great brunch for guests.

I’m not sure what I expected from MFK’s recipe for “War Cake.†A cake recipe from the first world war that had no eggs, no milk and no butter to me spelled nothing but bland and texture-deprived. Fisher’s undersell of the “crude, dark. moist loaf†did not help to bolster my enthusiasm: “I’m sure I could live happily without tasting it again,†she writes. Still, on its name, its history and its mystery. I had to give it a try.

I’m not sure what I expected from MFK’s recipe for “War Cake.†A cake recipe from the first world war that had no eggs, no milk and no butter to me spelled nothing but bland and texture-deprived. Fisher’s undersell of the “crude, dark. moist loaf†did not help to bolster my enthusiasm: “I’m sure I could live happily without tasting it again,†she writes. Still, on its name, its history and its mystery. I had to give it a try.  The recipe is curious; you boil shortening (you can use bacon grease, which was tempting, but I decided against it), with water, sugar, dried fruits (I went old-school with prunes and dates) and spices, let this liquid concoction cool, then mix it with flour and baking soda. Truly basic, it baked up into a delightful shiny loaf. The flavor was like a gingerbread; the texture, very moist. I made this twice and took one loaf to co-workers, who went wild over it. I would make it again, thinking of MFK dreaming of the cake as a child, loving it enough to share it as an adult. Beyond reading her, baking her spicy “odorous†cake, took me to a deeper level of connection.

The recipe is curious; you boil shortening (you can use bacon grease, which was tempting, but I decided against it), with water, sugar, dried fruits (I went old-school with prunes and dates) and spices, let this liquid concoction cool, then mix it with flour and baking soda. Truly basic, it baked up into a delightful shiny loaf. The flavor was like a gingerbread; the texture, very moist. I made this twice and took one loaf to co-workers, who went wild over it. I would make it again, thinking of MFK dreaming of the cake as a child, loving it enough to share it as an adult. Beyond reading her, baking her spicy “odorous†cake, took me to a deeper level of connection.

“How to Cook a Wolf†was a book I did not want to end. Dipping into it each day was like having a pleasant and inspiring chat with a brilliant friend who can take any topic and turn it into the most marvelous tale. I understand the kinship other food writers must feel with MFK Fisher (whether or not this was her intention, it happened, nonetheless) and how they look to her, not for ingredients or recipes, but for soul and wit. Reading MFK Fisher, I think I would find that any wolf — representing any hunger — sniffing at my door, is banished. With her on my bookshelf, I will never cook alone.

Eggs in Hell

From “How to Cook a Wolf†by MFK Fisher (1942)

4 Tablespoons olive oil (substitute will do, dad blast it)

1 clove garlic

1 onion

2 cups tomato sauce (Italian kind is best, but even catsup will do if you cut down on spices)

1 teaspoon minced mixed herbs (basil, thyme)

1 teaspoon minced parsley

Salt and pepper

8 eggs

Slices of French bread, thin, toasted

Heat oil in a saucepan that has a tight cover. Split garlic lengthwise, run a toothpick through each half, and brown slowly in oil…Add the onion, minced and cook until golden. Then add the tomato sauce and the seasonings and herbs. Cook about fifteen minutes, stirring often, and then take out the garlic.

Into this sauce break the eggs. Spoon the sauce over them, cover closely, and cook very slowly until eggs are done, or about fifteen minutes. (If the skillet is a heavy one, you can turn of the heat and cook in fifteen minutes with what is stored in the metal.)

When done, put the eggs carefully on the slices of dry toast, and cover with the sauce. (Grated Parmesan cheese is good on this, if you can get any.)

War Cake

From “How to Cook a Wolf†by MFK Fisher (1942)

½ cup shortening (bacon grease can be used, because of the spices which hide its taste)

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon other spices…cloves, mace, ginger, etc….

1 cup chopped raisins or other dried fruits…prunes, figs, etc.

1 cup sugar, brown or white

1 cup water

2 cups flour, white or whole wheat

¼ teaspoon soda

2 teaspoons baking powder

Sift the four, soda and baking powder. Put all the other ingredients in a pan, and bring to a boil. Cook five minutes. Cool thoroughly. Add the sifted dry ingredients and mix well. Bake 45 minutes or until done in a greased loaf-pan in a 325-350 degree oven.

Blogger’s note: I added a dash of salt in with the spices. I also used all brown sugar and half white flour and half wheat flour each time I made this cake.