Gravy is not good for you.

Let’s get that out of the way up front. I’m about to rhapsodize on one of my favorite things in the world, and I know very well that it is terribly unhealthy, excessively detrimental to one’s blood vessels and waistline, and has little or no nutritionally redeeming factors.

But boy, is it good!

I dabble in gravy occasionally. It is a sin I allow myself. There are so few left. Despite the trail of treats represented on this blog, I can tell you that AWS does not consume a high amount of sugar or fat. She doesn’t smoke or drink alcohol or do any kind of drug. She exercises hard and regularly. So remorse will never accompany her gravy (although drinking it from a glass, as she has been tempted to do, would likely indicate some sort of problem). It is both an indulgence and a right, held in high regard and eaten without an ounce of guilt.

Gravy is two things: fat-based and fluid.

That is my definition, but it’s not really the proper one. If you want to delineate by name all the things that are fat-based and fluid you could include everything from brown and white (béchamel) sauces to salad dressing. So I consulted a master tome, “The Joy of Cooking,†(a hugely voluminous cookbook with print so small it would challenge a Lilliputian to break out her magnifying glass), which clarified that “gravy†proper is a sauce made with the pan drippings of meat or poultry that has been roasted or fried. I still contend that fat and fluid do describe gravy, and any sauce can be called gravy for the want of a better name. And what a better name could there be?

Gravy is two other things: instinct and practice.

I come from a long line of gravy makers. It was a tradition practiced over and over again until the proper instinct came. The gravy at our table came in many forms. It was the pure, aromatic juice from roasted pork or beef in which potatoes and carrots swam. It was hamburger and onions fried and thickened with a flour roux, then swathed in milk and seasoned with salt and pepper, and then the whole deal spread over buttered biscuits for breakfast…or for lunch. It was a thicker measure of this same milk-based gravy – so thick in fact, my father claimed you could stand a spoon up on it – that was pebbled with the crunchy leavings of freshly fried chicken and liberally spiced with black pepper that would top mounds of whipped potatoes. Gravy was omnipresent – filled the skillets and perfumed the atmosphere — and gravy was good.

Gravy can appear out of thin air.

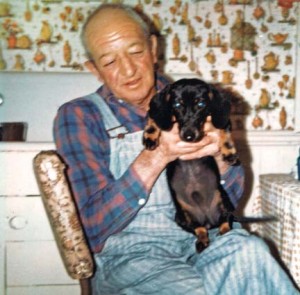

My Grandpa Merwin Howard made gravy out of nothing, or so it seemed. This whole event has become legendary in at least our branch of the family. Grandpa Merwin had a magic about him, so conjuring gravy from nowhere should have really come as no surprise. One year, he urged nearly 20 of us from the warmth of a Christmas dinner table to an old elm tree in 30-degree woods where he had found a bee hive (his later years were spent predominantly wandering and falling asleep in the timber), and where he dipped long bare fingers in the golden honey that had been made in said tree and laughed soundlessly as bees stung his bald head. He was magic. So one Fourth of July, as we downed potluck fare in my grandparents’ backyard, he pronounced to no one but himself, but pronounced loudly, as his hearing aid aided him only enough that his conversations were yelling on his end of them, that he wanted some gravy. We all chuckled. Grandma, ever mocking, decried that no pan drippings existed in the house and there was certainly no gravy mix and even if there was, that would not be the route Grandpa would go. Still, in about 15 minutes he came out of the house with a bowl of gravy to an audience of stunned and slack-jawed relatives. It seemed it would have been easier to have pulled a rabbit out of a hat (actually, it would have), and he never gave up how he did it. He ate his gravy without sharing it. Later, he contentedly resumed lighting firecrackers from his hand-rolled cigarettes and tossing them under his daughter-in-laws’ lawn chairs.

My Grandpa Merwin Howard made gravy out of nothing, or so it seemed. This whole event has become legendary in at least our branch of the family. Grandpa Merwin had a magic about him, so conjuring gravy from nowhere should have really come as no surprise. One year, he urged nearly 20 of us from the warmth of a Christmas dinner table to an old elm tree in 30-degree woods where he had found a bee hive (his later years were spent predominantly wandering and falling asleep in the timber), and where he dipped long bare fingers in the golden honey that had been made in said tree and laughed soundlessly as bees stung his bald head. He was magic. So one Fourth of July, as we downed potluck fare in my grandparents’ backyard, he pronounced to no one but himself, but pronounced loudly, as his hearing aid aided him only enough that his conversations were yelling on his end of them, that he wanted some gravy. We all chuckled. Grandma, ever mocking, decried that no pan drippings existed in the house and there was certainly no gravy mix and even if there was, that would not be the route Grandpa would go. Still, in about 15 minutes he came out of the house with a bowl of gravy to an audience of stunned and slack-jawed relatives. It seemed it would have been easier to have pulled a rabbit out of a hat (actually, it would have), and he never gave up how he did it. He ate his gravy without sharing it. Later, he contentedly resumed lighting firecrackers from his hand-rolled cigarettes and tossing them under his daughter-in-laws’ lawn chairs.

Gravy is a ritual, a meditation.

When I think of what I inherited from Grandpa Merwin, my obsession with gravy might be one of the things he imparted. Every Thanksgiving for certain, and often on Christmas and Easter, I set aside my time and focus solely for the gravy. It is a meditative and anticipatory process, lengthy but well worth it. I usually make one of my two favorite gravies – ham or turkey. As the turkey roasts, I take the giblets and neck from the turkey, toss them into a pot with celery, onion, garlic, dried herbs like oregano, fresh herbs like rosemary, thyme and sage, salt and pepper and I fill the pot with water and heat on low to medium heat. I let everything simmer to extract all the flavors.

When I think of what I inherited from Grandpa Merwin, my obsession with gravy might be one of the things he imparted. Every Thanksgiving for certain, and often on Christmas and Easter, I set aside my time and focus solely for the gravy. It is a meditative and anticipatory process, lengthy but well worth it. I usually make one of my two favorite gravies – ham or turkey. As the turkey roasts, I take the giblets and neck from the turkey, toss them into a pot with celery, onion, garlic, dried herbs like oregano, fresh herbs like rosemary, thyme and sage, salt and pepper and I fill the pot with water and heat on low to medium heat. I let everything simmer to extract all the flavors.  I make some stock using a dried bouillon powder (thus controlling the salt) and keep it nearby for later. This year, I had some shallots, so I chopped those up and sautéed them in butter, then added flour to make a roux. My holy grail of turkey drippings are then added, as is some Marsala wine leftover from a chicken dish I had made (normally, AWS keeps a booze-free zone, even in cooking, but sometimes wine is necessary for some preparations). Once the drippings and wine begin to bubble, I strain in the turkey/veggie stock and add chicken stock as needed until the gravy is a proper consistency. All other aspects of the meal are neglected – momentarily – as I am lost in the swirling richness on the stove. Suddenly, an inspiration…I add a tablespoon of Dijon mustard! This twang lends a little punch to the gravy, which I use to bathe turkey, stuffing, potatoes and sandwiches the next day

I make some stock using a dried bouillon powder (thus controlling the salt) and keep it nearby for later. This year, I had some shallots, so I chopped those up and sautéed them in butter, then added flour to make a roux. My holy grail of turkey drippings are then added, as is some Marsala wine leftover from a chicken dish I had made (normally, AWS keeps a booze-free zone, even in cooking, but sometimes wine is necessary for some preparations). Once the drippings and wine begin to bubble, I strain in the turkey/veggie stock and add chicken stock as needed until the gravy is a proper consistency. All other aspects of the meal are neglected – momentarily – as I am lost in the swirling richness on the stove. Suddenly, an inspiration…I add a tablespoon of Dijon mustard! This twang lends a little punch to the gravy, which I use to bathe turkey, stuffing, potatoes and sandwiches the next day

Gravy can come alive with a few twists.

Here are some of the things I’ve found that will lend a flavorful twist to gravy — as well as the tablespoonful of Dijon mustard, I have added mushrooms, apple cider, honey or jam (for ham gravy), red or white wine vinegar, fresh herbs, red pepper flakes, bacon. Be inventive and think what tastes you like – search your refrigator and cupboards — that would take your divine sauce just a note further in flavor.

Gravy (thickening it, that is) is a balancing act.

I once watched a high school chum of mine (yes, high-school girls from Kansas make gravy…we just do) enter into an endless tag team of flour ball-to-milk until she, giggling all the way, finally found the right consistency and heat enough to cook the dough dumplings out of her milk gravy. It’s a balancing act, friends, one to be entered into delicately and with patience. Your fat/drippings must be hot to take on the thickener of flour and you must administer the proper amount of flour and the proper time and work it in immediately and quickly and then know when to add the liquid (i.e. stock). The thickening agent can be added later, as well, in the form of cornstarch dissolved in a little water and added to the boiling brew of gravy…

Gravy should not be clear – especially if you can see your biscuits through it.

I have taken a chance on restaurant gravy and it is nearly always a 50/50 proposition. A restaurant in Venice, Calif., called The Dandelion Café (sadly, no longer in business), served the most outstanding hot turkey sandwich slathered in a mustard-infused gravy (the source for my Thanksgiving inspiration) that was a favorite of mine (the hot turkey sandwich is a much sought-after-but-seldom-on-the-menu dream of mine…it is such a beautiful thing). And I have had clear gravy, when gravy should not be clear, atop biscuits with bits of sausage suspended in it’s gluey grayness like dirty snow on a winter windshield. Not good. Most restaurant gravies exude an institutional flavor, as if they were concocted from a powdered mix or summoned from a can. I have been met by morning café platters so flooded with sausage gravy, I had to plumb the depths to find the biscuits, hash browns and eggs beneath. This can be a good or bad thing depending on the gravy. Or what are they hiding here? Is the gravy boat half empty or half full? I will continue to sample gravy from the menu. One can always have hope.

Gravy is a feeling, not a recipe.

I could have written up some instructions here, with this amount of pan drippings and that amount of stock and add so much of this seasoning or that, but, truth be told, every gravy I make – and I think I can find many who might agree – is as individual and unique as a snowflake. You use what you have to generate this magical sauce, and when it’s right, it’s right. A little practice and you’ll know it.

I could have written up some instructions here, with this amount of pan drippings and that amount of stock and add so much of this seasoning or that, but, truth be told, every gravy I make – and I think I can find many who might agree – is as individual and unique as a snowflake. You use what you have to generate this magical sauce, and when it’s right, it’s right. A little practice and you’ll know it.

You can feel good gravy in your bones.