I have had the privilege of attending many powwows and from my first time at one, I’ve sought them out around California. I go for many reasons, not the least of which is that I find going resets my heart to a rhythm matching that of the drums and dancers. I find this beat preferable to any other, to be sure.

I have had the privilege of attending many powwows and from my first time at one, I’ve sought them out around California. I go for many reasons, not the least of which is that I find going resets my heart to a rhythm matching that of the drums and dancers. I find this beat preferable to any other, to be sure.

I also go for the frybread.

I love frybread, have from the moment I tried it — a fresh hot slab of fleshy fried dough, puffed and golden, at least 10 inches across and drizzled with honey. To me, it has always tasted remarkably like a yeast dough, though I learned later it is not. But it resembles the fried bread my mother sometimes made from her white yeast dough, a creation she had always called “skonkz” (see blog entry, “Handing down a roll recipe,” 6/12).

So I went to powwows whenever I could, rekindled my soul and aimed myself at the the bread stations for a fry fix. Two years now, I’ve readied myself for the frybread at a local powwow. Two years, I have been disappointed. The first year had some glitch hangup the frybread station and no bread was ready to be served well past noon and the waiting line extended out into the street.

And this year, there was no local powwow, postponed for reasons yet to be revealed. I went as far as the state fair looking for frybread (as I had found it at the LA County Fair once), but only found fried Twinkies and well, innumerable other fried items (blog to come). No fry bread.

I was a blogger with a bread-of-the-month project and a salivary Jones for frybread. Naturally, the only choice was to make it myself.

After looking at a number of recipes from a number of sources, I settled on one from an article and cookbook from the Smithsonian Institution, home of the National Museum of the American Indian.

According to the article, the history of fry bread in American Indian culture is somewhat recent and somewhat controversial. Frybread came into being within the last 150 years, when Indians were “relocated” from the lands and lifestyles they were used to and began living on reservations. Out of the basic staples given to them from the U.S. government — flour, salt, sugar and lard — came the ingredients to create frybread.

Impoverished cultures have often found subsistence on versions of frybread — note the references to fried dough John Steinbeck makes in “The Grapes of Wrath,” his 1939 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about dispossessed Okies struggling to survive as they migrated across the country to California. Whatever one could create out of what one had kept you going.

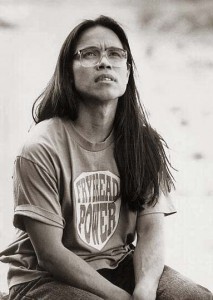

American Indian writer Sherman Alexie has said, “Frybread is the story of our survival.” The bread is symbolized and rhapsodized in the film Smoke Signals written by Alexie from one of his short stories. In the film, a character named Thomas Builds-the Fire wears a shirt reading “Frybread Power,” and tells a story of the magic of fry bread.

For more on the film and Sherman Alexie’s work, click here.

The only way the composition of frybread could be any simpler was if it was made of flour and water. As it stands, the recipe I chose was a mere blending of flour, baking powder, salt and warm water.

The only way the composition of frybread could be any simpler was if it was made of flour and water. As it stands, the recipe I chose was a mere blending of flour, baking powder, salt and warm water. I mixed it by hand (I will use any excuse to get my hands in dough) and kneaded it just until it came together. Any dough seems to benefit from a little rest — I gave mine a good half an hour covere with a towel. Then I formed it into an oblong roll as instructed and divided the roll into sections.

I mixed it by hand (I will use any excuse to get my hands in dough) and kneaded it just until it came together. Any dough seems to benefit from a little rest — I gave mine a good half an hour covere with a towel. Then I formed it into an oblong roll as instructed and divided the roll into sections.

I heated peanut oil in my old friend, my cast iron skillet, which had fried everything from tomatoes and okra to catfish and chicken, but would now give an inaugural scalding to some dough. As the oil heated (on medium to medium-high heat), I took a couple of the sections and flattened and pulled them into discs of about 5 inches in diameter.

As the oil heated (on medium to medium-high heat), I took a couple of the sections and flattened and pulled them into discs of about 5 inches in diameter.

Two dough discs could fit in the pan, but I decided to play it safe and let each disc go solo, so as to not lower the oil temperature and allow for even cooking. Upon hitting the oil, those small, flat circles swelled immediately into some other incarnation, triple in size. Its growth to such substantiality suddenly weighed with significance.

In about four minutes, I had my first piece of fry bread, hot and fresh and right in front of me. I would take full advantage of my cook’s privileges and dig in. There it was that long, longed-for heat, crispy  golden and chewy. It needed no topping or accessory. I was satisfied at last.

golden and chewy. It needed no topping or accessory. I was satisfied at last.

It didn’t take long to have a dish piled high with frybread. Part of my plan for the bread was to create another powwow concoction with it — Indian Tacos. Piled with seasoned ground turkey, lettuce, salsa and cheese the bread became something else — a meal.

Frybread

(From Smithsonian magazine, July 2008)

3 cups all-purpose flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

1 teaspoon salt

1 1/4 cups warm water

Extra flour for processing

(Yield: 8 to 12 small portions or 6 to 8 larger portions)

Directions:

To make the dough thoroughly blend the flour with the baking powder and salt in a mixing bowl or on a suitable, clean working surface. Make a well in the center of the flour mixture and pour the warm water in the center of the well. Work the flour mixture into the water with a wooden spoon, or use your hands. Gently knead the dough into a ball and form it into a roll about 3 inches in diameter. Cover the dough with a clean kitchen towel to prevent drying and let the dough relax for a minimum of 10 minutes. This dough is best used within a few hours, although it may be used the next day if covered tightly with plastic wrap, refrigerated, then allowed to warm to room temperature.

To form the bread, place the dough on a cutting board. Cut the dough with a dough cutter or knife into desired thickness. This process of cutting helps keep your portion sizes consistent. Naturally, you will want to cut small pieces for appetizers (or, alternatively, if you are making sandwiches, cut them bigger). Once you have determined the size, begin cutting in the center of the roll and continue the halving process until all of the portions have been sliced. Cover the pieces of dough with a dry, clean towel while you process each piece to prevent drying. Place some flour in a shallow pan to work with when rolling out the dough. Lightly dust each piece of dough and then place the dough on a lightly floured work surface. With a rolling pin, roll each piece to about 1/4-inch thickness. Place each finished piece in the flour, turn and lightly coat each piece, gently shaking to remove the excess flour. Stack the rolled pieces on a plate as you complete the process. Cover with a dry towel until ready to cook.

To cook fry bread, place any suitable frying oil in a deep, heavy pan. The oil should be a minimum of 1 inch deep. Place pieces of bread in the oil. Do not overcrowd the pan. Cook 2 to 3 minutes per side. This bread generally does not brown and should be dry on the exterior and moist in the center. Try cooking one piece first, let it cool, and taste for doneness. This will give you a better gauge of how to proceed with the balance of the bread, ensuring good results. Place the finished breads on a paper towel to absorb excess oil. Serve this bread immediately after cooking.

To make grill bread, place the bread on a clean medium hot grill. When bubbles form and the dough has risen slightly, turn the bread over to finish cooking. The bread is done when the surface appears smooth and is dry to the touch. Cooking time will vary but plan on approximately 2 to 3 minutes per side. This bread cooks quickly and is best when moist in the center, with a pliant crust. Some browning occurs, but generally speaking, this is a blond bread.

From “Foods of the Americas: Native Recipes and Traditions” by Fernando and Marlene Divina and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. © 2004 Smithsonian Institution and Fernando and Marlene Divina.