[T]ime was, a simple pizza crust would do. I came of age when I saw this concept turn. I grew up in the land of Pizza Hut, and after the advent of pan pizzas and personal pan pizzas, there began an onslaught of pizza crust one-uppings in every chain in America, where all manner of crust re-interpretations brought out the beast. Stuffed crust, double crust, double-stuffed crust, stuffed with cheese, stuffed with meat, stuffed now with, what, chicken wings? I’ve stopped keeping track and have frankly, been turned off.

[T]ime was, a simple pizza crust would do. I came of age when I saw this concept turn. I grew up in the land of Pizza Hut, and after the advent of pan pizzas and personal pan pizzas, there began an onslaught of pizza crust one-uppings in every chain in America, where all manner of crust re-interpretations brought out the beast. Stuffed crust, double crust, double-stuffed crust, stuffed with cheese, stuffed with meat, stuffed now with, what, chicken wings? I’ve stopped keeping track and have frankly, been turned off.

When I order pizza, I want my crust to be crust alone and not serve as a side dish to the pizza. There should be a balance and harmony between the bottom of the pizza and the top. And never too thick — if I wanted a loaf of bread, that’s what I would be eating.

It’s long been expressed in cookbooks and beyond that making pizza dough is one of the simplest things in the world. I’ve resisted, namely because I became hooked on the ready-made pizza dough sold in the refrigerator section at Trader Joe’s. After sitting out a room temperature a bit, this dough can be stretched into a delightful base where one’s creative topping ideas can bloom. The results are delicious, controlled by the maker who has say over the amount of sauce, sausage and cheese.

It’s long been expressed in cookbooks and beyond that making pizza dough is one of the simplest things in the world. I’ve resisted, namely because I became hooked on the ready-made pizza dough sold in the refrigerator section at Trader Joe’s. After sitting out a room temperature a bit, this dough can be stretched into a delightful base where one’s creative topping ideas can bloom. The results are delicious, controlled by the maker who has say over the amount of sauce, sausage and cheese.

Fashioning these pizzas “from scratch,” I’ve felt jaunty pride that I was making a “homemade” pizza, but knew that this was not quite. I needed to try to make a crust of my own. I had succeeded at a number of yeast doughs, and that is all pizza dough is, the most very basic of yeast doughs.

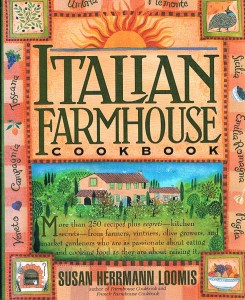

I consulted a number of resources for pizza dough recipes, but the one that struck my fancy for its purity and simplicity was Maria’s Pizza Dough, from the lovely “Italian Farmhouse Cookbook,” by Susan Hermann Loomis (2000). According to the book, Maria Maurillo’s dough, served to guests on her farm near Assisi, is very versatile, used not only for pizza, but for all sorts of goodies like little fried dough appetizers, and the author even used it to make rolls and loaves.

It is made with a substantial amount of olive oil,and after making it myself, I agree with the cookbook’s author that this is the element that makes this dough so user- and eater-friendly. It shapes nicely, browns evenly to a beautiful golden brown, and the thin-crust pizzas I made had a very tender, yet crisp flavorful base.

It is made with a substantial amount of olive oil,and after making it myself, I agree with the cookbook’s author that this is the element that makes this dough so user- and eater-friendly. It shapes nicely, browns evenly to a beautiful golden brown, and the thin-crust pizzas I made had a very tender, yet crisp flavorful base.

The dough is comprised of flour, dry yeast, water, olive oil and salt. It comes together quite easily; I used the dough hook of my Kitchen Aid mixer to knead. After one rising (about an hour and a half), the dough can be punched down and shaped for use. At this stage, I decided to try an experiment, based on my admiration of the refrigerator-friendly Trader Joe’s dough. I divided the dough into two rounds, put each into a Ziploc bag and stored them in the fridge for use over the next two nights.

The dough is comprised of flour, dry yeast, water, olive oil and salt. It comes together quite easily; I used the dough hook of my Kitchen Aid mixer to knead. After one rising (about an hour and a half), the dough can be punched down and shaped for use. At this stage, I decided to try an experiment, based on my admiration of the refrigerator-friendly Trader Joe’s dough. I divided the dough into two rounds, put each into a Ziploc bag and stored them in the fridge for use over the next two nights.

Crust seems easy. The toughest part of making pizza is deciding what should go on top. Twenty-four hours after refrigerating my dough. I came up with my first pizza: cremini mushrooms, bacon and red onion…working title: Pizza di Rebecca.

The dough held up well in the fridge, slid out of its bag easily with its glossy, oily texture. It rolled out well, too, to fit nicely in the pizza panI’ve had for years, a 13-inch, nonstick round with holes all over the bottom for more even browning.

I coasted the crust with a little olive oil, then a slight smearing of jarred pasta sauce, some mozzarella, then my bacon and mushrooms, which had been cooked together so that the mushrooms would absorb all the baconness. Then, some thin slices of fresh red onion. What a delicious pizza! Nothing overwhelmed anything else; all flavors were subtle and companionable and the fresh onion gave a textural crunch, along with sweetness. I liked the thin crispiness of the crust (for a thicker crust from the dough recipe, use all for one pizza rather than two).

I coasted the crust with a little olive oil, then a slight smearing of jarred pasta sauce, some mozzarella, then my bacon and mushrooms, which had been cooked together so that the mushrooms would absorb all the baconness. Then, some thin slices of fresh red onion. What a delicious pizza! Nothing overwhelmed anything else; all flavors were subtle and companionable and the fresh onion gave a textural crunch, along with sweetness. I liked the thin crispiness of the crust (for a thicker crust from the dough recipe, use all for one pizza rather than two).

Two nights after my initial dough making, I used my second round for my next creation — working title: Garden Herb Pizza. On this version, I used my usual base of olive oil and a little jarred sauce, as well as a small amount of mozzarella cheese. Then, I topped with thin slices of tomato and zucchini and dollops of ricotta cheese. What made this pizza a standout, I believe, is that I topped it with freshly picked rosemary and oregano.  Fresh oregano is bold, gutsy really, but a little lavished on a pizza top made it something special. The veggies were substantial, but balanced by the delicate creaminess of the ricotta. The tomatoes roasting on top imparting a little juice to everything. Despite that moisture, the crust was golden and sturdy beneath.

Fresh oregano is bold, gutsy really, but a little lavished on a pizza top made it something special. The veggies were substantial, but balanced by the delicate creaminess of the ricotta. The tomatoes roasting on top imparting a little juice to everything. Despite that moisture, the crust was golden and sturdy beneath.

You never know when the pizza cravings will call, but a call for pizza need not be made. I will try freezing the dough next. Pizza possibilities await.

Maria’s Pizza Dough

From “Italian Farmhouse Cookbook” by Susan Hermann Loomis (2000)

Makes about 2 pounds of dough, enough for 1 thick or 2 thin pizza or focaccia crusts

1 1/3 cups lukewarm water

2 teaspoons active dry yeast

1/2 cup extra virgin olive oil

4 to 4 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

1 tablespoon fine sea salt

In a large bowl or the work bowl of an electric mixer, whisk together the water and yeast. Add the oil and mix well. Add 1 cup of the flour and mix until smooth. Stir in the salt and enough of the remaining flour to make a soft dough. Because of the oil, the dough will feel somewhat slippery, and it may not be a homogenous lump at first. Knead, adding a little flour as necessary, until it comes together and is satiny and elastic, about 5 minutes. The dough should be moist because of the oil but not wet, and it shouldn’t stick to your clean finger.

Place the dough in a clean (unsoiled) bowl, cover with a tea towel, and let rise at room temperature (68 to 70 degrees) until it is doubled in bulk, about 1 1/2 hours. Punch down dough and use in recipes as called for.

Blogger’s Note: For my thin-crust pizzas, I baked them at high heat — about 440 degrees — for approximately 15 to 17 minutes.