[I]f there is some truth to the notion that we pick our parents before we are born, then I must have selected mine because I knew they would lead me to morel mushrooms.

By lead, I mean literally. During my childhood in Kansas, I was taken on jaunts into timber so thick it seemed unnavigable and spent the length of warm spring days on the hunt for an elusive fungi that was as good as gold in our house. For all the scratches, nettle stings, insect bites, potential tramplings by herds of cows in pastures, endless miles walked, dirt and sweat and thirst, and grumblings about all of it, if it ended in a platter of the golden, crispy-fried morel nuttiness that makes me drool to ponder to this day, any discomfort was forgotten.

In spring, once it warmed to a certain temperature, it was all about mushroom hunting, whenever and wherever opportunity presented itself. Having an uncanny observance of the landscape, my parents knew the trees and knew which ones had died and also when they died and this status of decay predicted mushrooms.

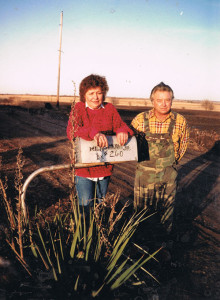

My mother and father have really been the two best guides on matters of the natural world. They are made of the stuff of our former days as humans; they have not lost touch with that knack and instinct and connection, unlike those of us in the modern age whose vein running to such things has ben severed and cauterized by convenience, ignorance, distraction and laziness. If a bird calls, they can tell you what it is (or even identify some mysterious splash in a creek), understand an animal track, sniff the air and make fairly accurate weather predictions. This is how people used to live.

They grew up hungry and had the skills to satisfy this need. I, in my young days, was the witness and beneficiary of this. They took us hunting and fishing, and captured bull frogs by flashlight from an aluminum row boat. We grew things to eat, but also picked them from the wild. Watercress from a running creek; morel mushrooms from the timber.

“Look down! Look down! They’re right in front of you!â€

The “shrooms†jutted like aliens out of dead leaves and branches blanketing dense thickets. Golden to gray in color, conical like Christmas trees from another planet, their real otherworldly detail, a covering of endless enlarged pores that almost make them seem like they had an animal skin.

While finding them proved a challenge for me, I fell in love with the taste of morel mushrooms. Coated in seasoned flour and fried crispy, I ate them like popcorn and longed for them when they were gone.

While finding them proved a challenge for me, I fell in love with the taste of morel mushrooms. Coated in seasoned flour and fried crispy, I ate them like popcorn and longed for them when they were gone.

Grown up and far-flung from my home, still pale and bespectacled, I have run across morels — not in the woods — but on restaurant menus (in cream sauce!?) and in gourmet shops (dried, about seven to a package, sold for $15). Not the same at all.

About eight years ago, I visited my parents in the spring and we went mushroom hunting one morning. I imagined, now that I was grown, that this would be some leisurely jaunt of parties on equal footing. How wrong I was. As we descended into a ravine thickened to near darkness with elm, oak, ash and dogwood trees — each of us carrying a paper sack for our take — I was shot back into my childhood. My parents, who had 25 to 30 ahead of me, had suddenly become fuel-injected by the wilds. They had separated and were quickly disappearing out of my view, slipping easily through the brush like snakes, while I struggled, dodging and tangling with every possible branch.

I spent the morning not so much looking for mushrooms, but trying to find my parents, whose mushroom mission had pretty much made them lose sight that I — who had sadly become citified — was still in their charge. They found mushrooms. I found my humility.

But later, the mushrooms my mother cooked made up for it. The fried mounded platter sat between my dad and I, munching away. My mother doesn’t even like to eat them! She just hunts. The cashew nuttiness, the flavor ranges between the size of the mushrooms. You can just sit there in silence and enjoy. Nothing else you can do. In the years that I have been unable to get back home in the spring, my mom has fried and frozen some for me.

But later, the mushrooms my mother cooked made up for it. The fried mounded platter sat between my dad and I, munching away. My mother doesn’t even like to eat them! She just hunts. The cashew nuttiness, the flavor ranges between the size of the mushrooms. You can just sit there in silence and enjoy. Nothing else you can do. In the years that I have been unable to get back home in the spring, my mom has fried and frozen some for me.

If only they were more available. To my knowledge, they only grow in the wild. Cultivating them has remained as elusive to man as their location often is. For as much that has been figured out about morels, no one has really tamed them.

They are gathered in wild spots and sold fresh in specialty markets. And they cost a pretty penny. And I confess  here and now that the urge for them has pushed me in this direction. Twice.

here and now that the urge for them has pushed me in this direction. Twice.

Recently, a dear soul brought me a small bagful from a mushroom purveyor in the San Francisco Ferry Building. I felt like a failure frying them, thinking of the hard work my parents put into acquiring morels, and here they could be bought and sold.

These mushrooms may have been cleaned, but out of respect for tradition (and bugs), I sliced them in half and gave them a good soaking in salty water, anyway. Then a dredge in seasoned flour.

Despite their origin, the mushrooms’ dusty, nutty aroma from my sizzling pan lifted me skyward and also sent me back in time, a journey not in waste.

Despite their origin, the mushrooms’ dusty, nutty aroma from my sizzling pan lifted me skyward and also sent me back in time, a journey not in waste.

I crunched them down, this time sharing them with the friend who bought them. The silent reverence still there on both our parts. Delicious, of course, even though they did not come from Kansas.

I was eating purchased morel mushrooms. Dear me. What had happened? What was being lost? Does the spore stop here?

I am not like my parents, even though I represent them in watered-down ways. But they were the guides who brought me here. They were not so much always reassuring as parents, but they gave me the natural world in which I still find reassurance. They taught me to adhere to a code of silence upon entering the wild places (I continue to be astounded at the loud human conversation and lack of attention when I’m on hikes and other outdoor jaunts). They showed me how to listen and how to watch.

astounded at the loud human conversation and lack of attention when I’m on hikes and other outdoor jaunts). They showed me how to listen and how to watch.

I would like to believe that, if set down in some woodsy space now on my own, some switch would be flipped and my genetic senses returned. I would sniff the air for decomposition, study the trees and know where to go from there. Without my guides? I don’t know.

Look down! Look down!

They are right in front of you.