“Never grow a wishbone, daughter, where your backbone ought to be.â€

— Jennie Paddleford to her daughter, Clementine

[H]ow is it possible that, in the four years I attended Kansas State University, majoring in journalism, spending two years working on the school’s daily newspaper, The Collegian, and even planning and putting together a weekly FOOD page, that I, in all that time, never heard of one of the university’s most famous graduates, a nationally known food writer named Clementine Paddleford?

Some 65 years before I attended Kansas State, so did Clementine, a farm girl from Stockdale, who also majored in journalism and worked for The Collegian, and like me, harbored very ambitious aims for her writing career.

Clementine made good on her ambitions. She had a thriving career spanning the ‘20s, ‘30s, ‘40s , ‘50s and ‘60s. It was a time where women were not dominant in the newspaper world, and the food section was merely a recipe page. Clementine took the recipe and made it not only a stepping stone, but a catapult for her career, where she became not just a food writer, but a roving food editor, and well-paid for her time at that. She forged a new kind of food writing — one that told the story behind the food. And she went out in the world to find those stories, first-hand. She made the writing descriptive, informative and human. At the peak of her career, she had a following of 12 million readers.

Clementine made good on her ambitions. She had a thriving career spanning the ‘20s, ‘30s, ‘40s , ‘50s and ‘60s. It was a time where women were not dominant in the newspaper world, and the food section was merely a recipe page. Clementine took the recipe and made it not only a stepping stone, but a catapult for her career, where she became not just a food writer, but a roving food editor, and well-paid for her time at that. She forged a new kind of food writing — one that told the story behind the food. And she went out in the world to find those stories, first-hand. She made the writing descriptive, informative and human. At the peak of her career, she had a following of 12 million readers.

Making a writer known

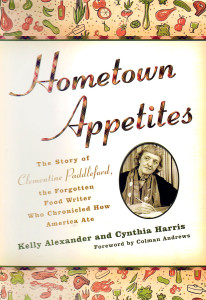

I first learned of Clementine Paddleford in a 2002 article by Kelly Alexander in Saveur magazine. Stunned and fascinated by the piece about a woman with whom I shared so much common ground, I wanted to know more. Apparently, so did Alexander. In 2008, she and Kansas State University archivist Cynthia Harris published the biography, Hometown Appetites: The Story of Clementine Paddleford, the Forgotten Food Writer Who Chronicled How America Ate

The book is a detailed examination of a life. Clementine picked up and left Kansas for New York shortly after her graduation in 1921. She spent a few years struggling but working hard, writing for various publications. She was bold, assertive and looking out for herself, and underlying it all was an unyielding and relentless work ethic and a BELIEF in the work she was doing. Clementine was once quoted as saying about her work: “It’s always important. It’s always interesting. I never find food or food materials dull.â€

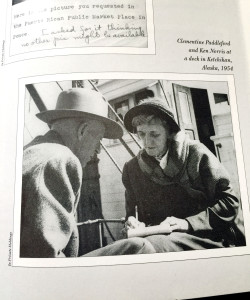

Clementine pushed forward with a career that, for her time, was astounding, She traveled around the United States and beyond, interviewing both professional and home cooks on their specialties for The New York Herald Tribune, and a weekly column in This Week magazine (she also contributed to Gourmet).

She interviewed the famous — travel writer Duncan Hines (yes, he was a real person!); Joan Crawford (who supplied Paddleford with her meatloaf recipe); and attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, where she wrote a series of columns on English food.

She was an adventurous sort, learning to pilot her own plane. She rode the rails of the Katy railroad dining car to learn the secrets of it’s featured crispy cornbread treats called “Kornettes.†She boarded the USS Shipjack in the Thames River in Connecticut to bring to the surface how the naval cadets aboard found sustenance, preparing “brownies for 80; hamburger pie for 100.†As for another submarine — a sub sandwich — Clementine coined the term”hero,” saying you had to be one to eat a sandwich that large.

She was an adventurous sort, learning to pilot her own plane. She rode the rails of the Katy railroad dining car to learn the secrets of it’s featured crispy cornbread treats called “Kornettes.†She boarded the USS Shipjack in the Thames River in Connecticut to bring to the surface how the naval cadets aboard found sustenance, preparing “brownies for 80; hamburger pie for 100.†As for another submarine — a sub sandwich — Clementine coined the term”hero,” saying you had to be one to eat a sandwich that large.

She also celebrated the home cook, who shared recipes “word-of-mouth hands down from mother to daughter,†writing of Kansas cooking clubs and Wisconsin housewives preparing authentic Swiss, Polish and Danish foods, like Polski Torte and Ebelskivers. She featured recipes from at the time newer states of Alaska and Hawaii. She celebrated teen-age prize-winning cooks who made their own pizzas.

“I have eaten every dish at the table where I found it,†she wrote in her introduction to her cookbook, “How America Eats.†(1960). She illuminated the food world through thousands of miles and nearly as many recipes.

Personal tragedies and triumphs

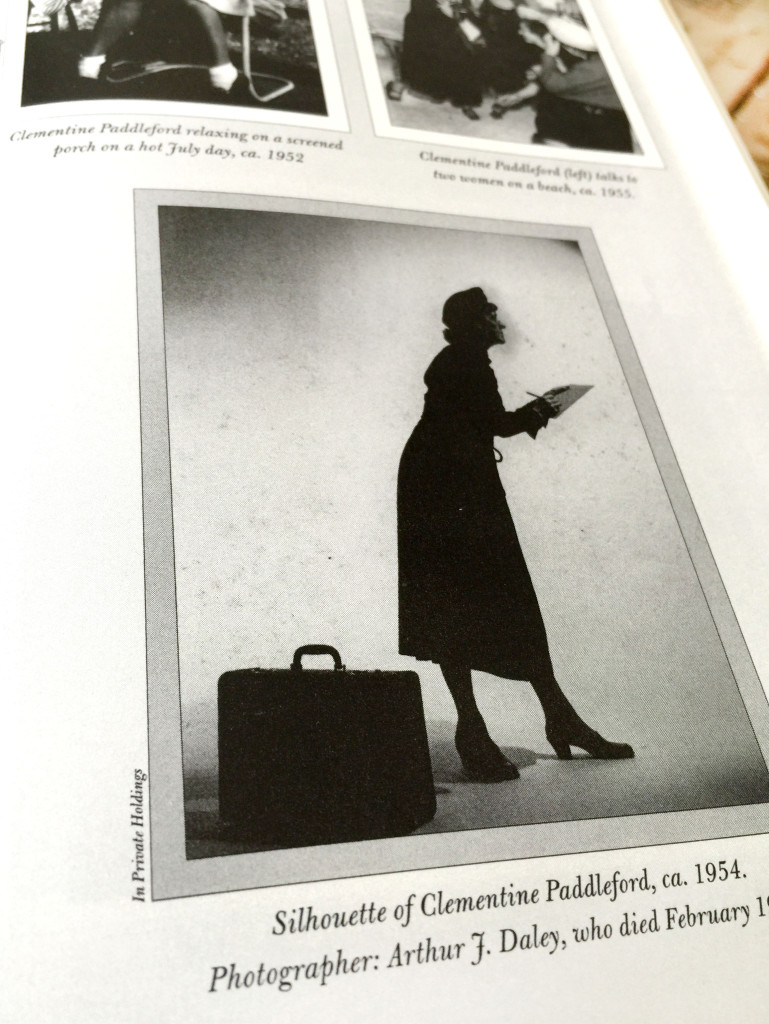

Clementine survived a near-fatal prognosis of throat cancer when she was just in her 30s. After her surgery, her voice was compromised and she disguised the breathing tube in her throat with a velvet choker. It barely slowed her down, however.

In a time when marriage and family were on nearly every woman’s docket, Clementine’s career was her priority. She married once, but never lived with her husband. She had a number of relationships, but never really settled down, except for her eventual adoption of a teen-age girl, whose mother — one of Clementine’s friends — died young.

Despite being proclaimed “best known food editor in the United States” by Time in 1953 (she even inspired a New Yorker cartoon), most people still don’t know who she is. For someone so prolific, how could this be? Alexander supposes it was Clementine’s place on the food timeline that put her in near-obscurity. Following her death in 1967, the food world entered a time of rapid evolution (and continues to change dramatically), Clementine’s New York Herald Tribune folded and restaurant critic Craig Claiborne and The New York Times began to dominate newspaper food writing. Julia Child went on television as “The French Chef,†and a stream of foodie successors followed. But some will argue, Clementine was the first of her kind and laid the foundation for all.

I can only believe that Clementine was following some bright star only she could see. I, as the most unfamous of unfamous food writers, stand in her shadow, but appreciate its long cast. As I read “Hometown Appetites,†I did not want her story to end. To know her more deeply, I decided to read more of her work, first-hand.

Clementine’s Recipe Road Book

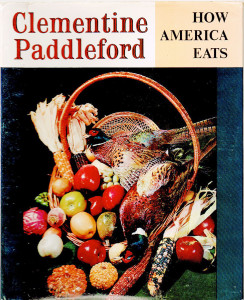

In 1960, her How America Eats

In 1960, her How America Eats columns culminated into a cookbook of the same name (a later, extended version called The Great American Cookbook

was published in 2011).

Last summer, traveling over the Fourth of July holiday, I plunged in and read the cookbook, cover to cover (the e-book…the published version — at 800 pages — is not very portable). It was as patriotic and American a book as any one could read, from start to finish.

Clementine’s intro to her book sizes it up in her words: “This book has been twelve years in the writing. It was in January 1948 I started criss-crossing the United States as roving Food Editor for This Week Magazine — my assignment, tell ‘How America Eats.’ I have traveled by train, plane, automobile, by mule back, on foot — in all over 800,000 miles.â€

“…I have ranged from the lobster pots of Maine to the vineyards of California, from the sugar shanties of Vermont to the salmon canneries in Alaska, I have collected these recipes from kitchens, apartment kitchenettes, governors’ mansions, hamburger diners, tea rooms and the from the finest chefs in charge. I have eaten with crews on fishing boats and enjoyed slum gullion at a Hobo Convention.â€

The book marries travel, food and cultural anthropology. She spent Christmas in Colonial Williamsburg: “The moment you are seated at the candlelighted table a waiter is tying a yard square napkin around your neck. Notice the table setting. China, silver, glass are in reproduction of Colonial table fittings. Water glasses are hand blown, knives have pistol handles, easy fitting to the hand, forks are three-tined. Spoons have a rat tail, where the handle fastens to the bowl.â€

She wrote of the origination of Smithfield ham, sauerbraten and shoo-fly pie. She attended Tennessee family church camp gatherings where: “Women gathered around to tell me who is who among the good Taylor cooks. They were eager to help me get recipes, believing there is nothing good to eat north of Washington.â€

She wrote of the origination of Smithfield ham, sauerbraten and shoo-fly pie. She attended Tennessee family church camp gatherings where: “Women gathered around to tell me who is who among the good Taylor cooks. They were eager to help me get recipes, believing there is nothing good to eat north of Washington.â€

Capturing the regional scene

The book is a portrait of an America, always changing, and one senses reading it, Clementine’s need to document what, at that time was traditionally “American.â€

“The pioneer mother created dishes with foods available,†Clementine wrote. “These we call regional. It’s to these, perhaps, I have given the greatest emphasis here.â€

As I paged through Clementine’s cookbook, I found those regional treasures she unearthed, which were, even in her time, subject to extinction. Reading about a shad fry under a maple tree in New Jersey, I wondered if such a tradition was still happening, and what a loss if it wasn’t:

“The shad were nailed to their planks, the planks one on another piled the garden bench. Bags of charcoal made a barricade to the south of the tree. Bill counted four pairs of white cotton gloves for firemen and plankers. He checked the salt and pepper in the big kitchen shakers. The night settled down. It threw a velvet blanket over the tree, turning the shad kitchen into a firelighted crypt.â€

Clementine’s prose was sometimes clipped and economical, sometimes bordering on flowery. I had no problem with the flowery, particularly reading what she wrote about wild plums in Nebraska:

“The ruby juice of the wild plum shines crystal clear, casting its little flames like prairie fires. the thick plum preserves are amethyst, unctuous and solemn, the peach a molten gold. Turn the contents of jars into cut glass bowls; spill out sunshine and the drone of bees, the wild plum blossom’s breath, sweet and strong, blossoming from a thicket along a deep ravine. Here is a fragrance of a a peach orchard spreading its pink and white banner of bloom to the soft May breeze. Some crafty kitchen alchemist has caught the blue and gold of summer and turned it into shining jewels to be enjoyed now when days go dull, when snow is falling and icy patterns form on bluish window panes.â€

I’ve never read a cookbook like a narrative, but I found myself urged on as I read “How America Eats.†I was done with it quickly, left standing at the roadside as if I had traveled those many miles with Clementine and still looking down the road hoping to see her again.

Cooking from it has been a slower process, in that I wanted to choose a few things to share (more to come later) that stood out as representative of Clementine’s work and would also be both unique and appealing to try. The cookbook is dessert heavy, LOADED with cookies, pies and cakes, so I chose a pie and a cake here. I picked a bread (flapjacks) that will be featured in my May“Bread of the Month†entry.

Cooking from it has been a slower process, in that I wanted to choose a few things to share (more to come later) that stood out as representative of Clementine’s work and would also be both unique and appealing to try. The cookbook is dessert heavy, LOADED with cookies, pies and cakes, so I chose a pie and a cake here. I picked a bread (flapjacks) that will be featured in my May“Bread of the Month†entry.

Have you heard of Marlborough Pie? I had not either. It is a very old and traditional recipe from the Eastern United States. Clementine wrote of the “a glorification of everyday apple†pie: “I had heard about Marlborough pie, but never met one face to face.†So she traveled to Massachusetts and got two recipes from a Miss Susan L. Ball, who explained, “It’s the Marlborough for celebration, sharp of lemon rind and juice and thickened with eggs.â€

I loved the Marlborough’s delicate but bright apple flavor and its soft light texture. This would be a lovely pie to make a holiday tradition in any part of the country.

Deerfield Marlborough Pie

From How America Eats

by Clementine Paddleford (1960)

Makes one 9-inch pie

2 cups tart, applesauce, sieved

2 tablespoons butter or margarine, melted

1 cup sugar

1/2 teaspoon salt

3 tablespoons lemon juice

1 teaspoon grated lemon rind

4 eggs, slightly beaten

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 9-inch unbaked pastry shell (deep)

Combine applesauce, butter, sugar and salt. Add lemon juice and rind to eggs and stir into sauce. Stir until well-blended. Pour into pastry shell. Bake at 450 degrees F for 15 minutes; reduce heat to 275 degrees F and bake 1 hour or longer. The pie should be golden brown and cut like a custard pie.

I picked the next recipe because it seemed to be Clementine’s weakness, as she simply stated in her declaration: “Chocolate cake, ow that’s my meat.†She featured a few recipes, including this one from Pennsylvania, that began as a home recipe and was later featured in a restaurant. I discovered it to be a darkly rich cake that got better with time. In “Hometown Appetites,†Alexander teams the cake with a fudge icing also in the cookbook from Washington state that is made with cocoa and hot coffee.What I liked most is its single-layer size…if you have less than a crowd gathering, it’s nice to serve something smaller.

Aunt Sabella’s Black Chocolate Cake With Fudge Icing

Recipes adapted from How America Eats

by Clementine Paddleford (1960) for Saveur Magazine

Makes 1 8-inch square cake

For the cake:

2 oz. unsweetened chocolate,chopped

5 tbsp. plus 1 tsp. unsalted butter, softened

1 1/4 cups sifted flour

1 tsp. salt

1 tsp. baking soda

1 cup buttermilk

1 cup sugar

2 egg yolks

For the frosting:

2 1/4 cups confectioners’ sugar sifted

5 tbsp. cocoa

6 tbsp. unsalted butter, melted

5 tbsp. hot freshly brewed coffee

1 1/2 tsp. vanilla extract

Preheat oven to 350º. Melt chocolate in a small heatproof bowl set over a small pot of gently simmering water over medium-low heat, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon. Remove bowl from heat and set aside until chocolate is cool. Meanwhile, grease an 8″ square cake pan with 1 tsp. of the butter and set aside. Sift flour and salt together in a small bowl and set aside. Stir baking soda into buttermilk in another small bowl and set aside.

Beat sugar and the remaining 5 tbsp. butter together in a large mixing bowl with an electric mixer on medium speed until light and fluffy, about 2 minutes. Beat in egg yolks, then add melted chocolate and beat until thoroughly combined. Add one-third of the flour mixture, then one-third of the buttermilk mixture, beating well after each addition. Repeat process to use all of both mixtures, then pour batter into prepared pan and bake until a toothpick inserted in center of cake comes out clean, 40-50 minutes. Transfer cake to a rack to cool in pan, then invert onto a cake plate.

For the frosting: Sift confectioners’ sugar and cocoa together in a medium bowl. Stir in butter, then coffee, then vanilla, mixing well with a wooden spoon after each addition, until frosting is smooth. Ice top and sides of cake with frosting.

I chose this last recipe to represent the West and Clementine’s occasional foray into restaurants. Clementine wrote of the Palace Hotel “…no gourmet even today would think of visiting San Francisco today and not dining at the Palace.†Here is where Greek Goddess Dressing originated. A thick creamy concoction flavored with onion and herbs, it is delicious on mild or baby greens..and one day I hope to try it at its birthplace.

Greek Goddess Dressing

From How America Eats by Clementine Paddleford (1960)

Makes 1 3/4 cups

4 anchovy fillets, finely cut

2 tablespoons chopped onion

1 teaspoon chopped parsley

1 teaspoons chopped tarragon

2 teaspoons chopped chives

1 teaspoon tarragon vinegar

1 1/2 cups mayonnaise

Combine anchovy, onion, parsley, tarragon, chives and tarragon vinegar. Add mayonnaise; gently mix until blended. Serve over greens tossed together in a salad bowl rubbed with a cut clove of garlic.